This post originally appeared on my patreon in August. Subscribe today, if you want.

My tour through 80s/90s comics has brought me firmly into a reread of Grant Morrison written comics from that time period. For my birthday I got the big Doom Patrol omnibus that collects Morrison and Richard Case’s whole run, and it has been something of a revelation, as a lot of these comics from this time period are. I’m not really a stranger to Morrison’s work, when I got back into comics in high school, it kind of went Moore, then Miller, then Ellis, then Morrison, then Ennis at the front part of my journey. As you would. I think the Invisibles was probably a significant read in that time period, though I don’t really recall if I read the entire run(thus I am about to do a reread on that now)--anyways, point is, I’m pretty familiar with most of Morrison’s work with a few notable exceptions (Doom Patrol, Animal Man, and Zenith are probably the big ones). Even with that said, I was really suprised by Doom Patrol. From the Morrison front, I feel like one of the things he’s best at is turning comics into these kind of jagged poems spinning off into all directions, and one of the things he’s worst at is the kind of dense meta-narratives that say, someone like Moore carries off with ease. Morrison at his best is more of a poet, and Moore is more of a novelist in a lot of respects. Doom Patrol plays to those strengths.

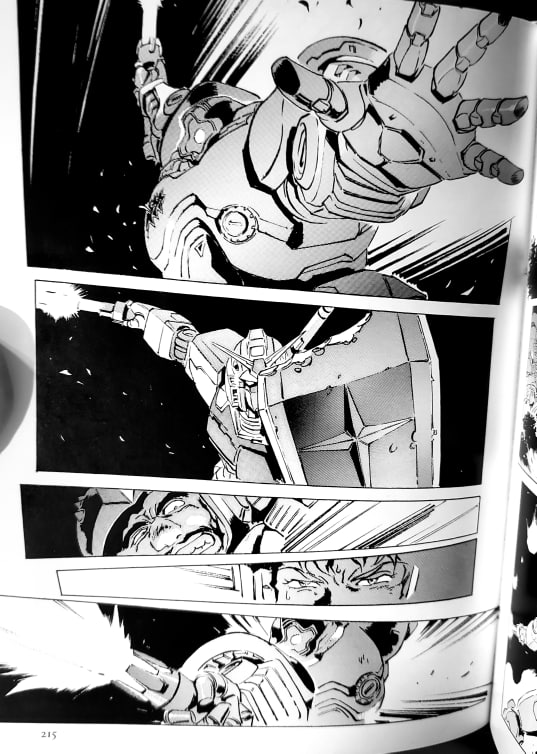

The real revelation though was Richard Case, whose work I was unfamiliar with before this. It’s wild all of the great artists who dropped in on Doom Patrol, whose work I like otherwise, like Kelley Jones, Shaky Came, Bisley, and many more--but they were all just distractions from Case. Whenever Case wasn’t on an issue it was really felt. I felt a legitimate yearning for his return even within the context of how fast you can whip through an omnibus. I found something in Case’s work on Doom Patrol that I feel has really been lost in comics today. Genuine honest to goodness cartooning coupled with an ability to draw any old weird thing pretty effortlessly. And with the crew of inkers (my favorite was Mark Badger) really put this expressive, textural, figurative art on the page. With really striking colors from Vozzo and Wolfman. And fucking hand lettering from John Workman, who is a fucking genius. Like full respect to digital letterers of the world today, but Workman’s handlettering on this book is as important as anything. I rarely kind of notice the lettering to this degree, and not in a bad way, just in a “wow, there’s a lot being carried by the letterer here” way. The way he’s able to move through the different characters from Crazy Jane and give each their own font, so you instantly know when she’s changed personality and sometimes even to which personality, is incredible work.

The heart of Doom Patrol is the notion of broken people outcast from society, healing with one another and learning to love themselves by caring for each other is fairly powerful, but I don’t know if it would have landed nearly as well without Case’s Cliff Steele. The most emotional raw nerve of the whole series is a man who is a brain trapped inside of a metal robot body, and yet somehow Case is able to both keep that rigid robot body horror prison thing on the page, while giving us the most expressive faces of the entire series. Cliff and to a lesser extent Jane are the emotional tent poles of the series, and it is Case’s depiction of them that makes that stuff hit. Case was born to draw Cliff. It’s like an actor who is just perfect for a part, Case so embodies Cliff on the page, that any other version of Cliff feels lesser. And so many great artists really did take their crack at Cliff, but I don’t think any of them hit it. Maybe Phillip Bond came the closest, but still just a shadow of Case’s. I mean look at these faces, look at how much emotion Case is getting out of this figure. It’s jaw dropping and truly inspiring.

I think one of the things I kept thinking about while I was reading Doom Patrol is how the standard in independent comics isn’t really high enough to pull this off right now, but how necessary comics like this really are right now. I also thought about the degree to which Doom Patrol is slightly restrained by having to fit within the superhero genre conventions, and how anytime it gets to a space where maybe there isn’t a bad guy to just punch, it gets pretty good. Like the whole section where Mr. Nobody runs for president, and actually what he’s trying to convince people of is kind of the right thing. I think the superhero stuff really only serves Doom Patrol as an excuse for greater weirdness, which I can appreciate more than an idea of grander hero worship that later Morrison books fall prey to. I don’t think any of my lasting images of Doom Patrol really have anything to do with the superhero genre. They’re Cliff pounding his head into a wall. Cliff asking Jane to come in out of the rain. That kind of thing. All of the Brotherhood of Dada stuff. The paranoia and weirdness of the flex mentallo stuff. Cliff dragging his upper torso through an apocalyptic nightmare. There’s not really a single hero punching a villian moment I really cared about or remembered.

So it would be interesting to see something with this kind of energy and execution done outside of the confines of the corporate comics structure. I guess in some respects that’s what The Invisibles is, but and I mean we’ll see, but I don’t remember The Invisibles having the same heart that Doom Patrol has. Doom Patrol expresses itself, where I remember a lot of the Invisibles just explaining itself. Also no Richard Case. So we’ll see.